Blog and News

An Archeology Lesson: On What We Leave Behind

- DateSeptember 11, 2015

- AuthorMary Heather

- Categories

- Discussion0 Comment

Today’s headlines are ablaze with exciting news: “Homo Naledi, A New Species in Human Lineage, Is Found in South African Cave,” says the New York Times. From NPR, “South African Cave Yields Strange Bones of Early Human-Like Species.”

Researchers in South Africa have discovered the remains of a new species of human ancestor, Homo naledi, a curious new creature with hands like ours, and who likely walked upright like us, but with much smaller bodies and much smaller brains. Who were these early people? How did they live, and why were the bones of so many individuals found so deep in this particular cave?

It’s interesting, this vocation of digging and discovering, playing detective with the clues we find in the earth. It seems to me to encompass the best of both phases of our lives: child-like exploration and imagination coupled with the applied intellect of adult retrospection.

A few months ago, during my residency at PLAYA in Summer Lake, Oregon, I was invited along with the other artists-in-residence to visit an archeological dig. The theme of our residency was focused on the collaboration of art and science, and we creatives were invited to see a little science in action.

Our host was University of Oregon archeologist Dr. Dennis Jenkins, whose own work in the Paisley Caves of southern Oregon has challenged the once widely accepted story of how and when early humans populated North America. His discovery of human coprolites (fossilized human excrement) radiocarbon dated between 14,000 and 14,300 years old, pre-dates previously discovered artifacts from the “Clovis people,” who were once believed to be the first North Americans via an Ice Age migration from Siberia through the Bering Straight. In essence, scientists have returned to the drawing board to understand the full story of how we got where we are.

Here’s what struck me most about the visit: 1) our continued fascination with the origin of our species juxtaposed against the increasing threat of our demise, and 2) the role of what we discard in the telling of both of these stories.

“You can learn a lot about a species,” Dr. Jenkins said, “from the waste it leaves behind.” He went on to explain how scientists can extract the DNA from plant and animal species found in human coprolites to re-imagine the environments in which our ancestors lived, right down to the lice in their hair.

“You can learn a lot about a species,” Dr. Jenkins said, “from the waste it leaves behind.”

This lesson stays with me.

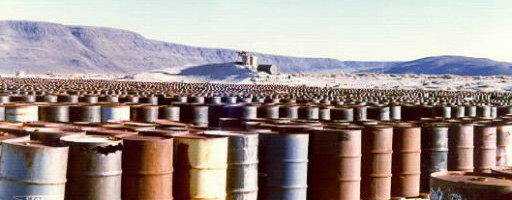

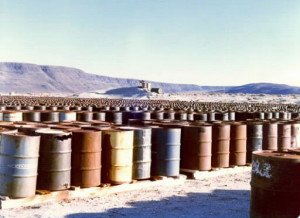

During my time at PLAYA, while reading about the plight of veterans seeking support from our government for their exposure to Mustard Gas and Agent Orange, I discovered, ironically, that just a few dozen miles (as the crow flies) from my environmental writing retreat, is the Alkali Lake Chemical Waste Disposal Site. An isolated, ten-acre site that contains the remnants of over 25,000 fifty-five-gallon drums of chemical waste, including dioxins and distillation residues from the production of Agent Orange and other toxic herbicides used during the Vietnam War.

In other words, a place not yet being studied as such, but one which meets all the basic criteria of an archeological site: any place where physical remains of past human activities exist. What might an archeologist learn about us upon discovering such a site? What does this waste say about our species? About our relationship to one another? About our relationship to the earth?

I did not visit the Alkali Lake site — public access is restricted for obvious reasons — but I have walked along the Summer Lake playa of the Oregon desert outback. My feet have sunk into the cookie-crumble soils of sun-baked playa shores. I know how thirsty they are when the thunderstorm clouds tease from above.

Between 1969 and 1971, over 25,000 drums of herbicide waste were transported from Portland-based Chemical Waste Storage and Disposition, Inc. to the Alkali Lake CWDS under a permit granted by the Oregon Department of Agriculture (ODA). Waste deliveries ceased in 1971, after the ODA and Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) determined that the company was improperly handling and disposing of chemicals at the site, leaving barrels unattended and leaking.

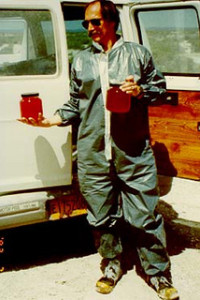

After a three-year legal battle, the DEQ assumed administration of the site, and in 1976 took action to crush and bury the rusting drums into twelve, 400-foot-long, 2.5-foot-deep trenches. You can see it being done here:

Bulldozers Puncture Drums of Toxic Waste at Alkali Lake, Oregon – YouTube

I know how thirsty those soils were. Now, ground water at the site is so contaminated that samples collected for analysis are bright red in color.

Red is the color of anger.

The DEQ still monitors the site, but has abandoned administrative action to pursue remediation. Veterans continue to fight for compensation for the health effects from their exposure to Agent Orange. So for now, this site is remains a relic, an artifact of the harm we are willing to inflict upon ourselves. For what, exactly?

For victory?

For profit?

I keep hoping for another Dennis Jenkins — a Dennis Jenkins of the environmental archeology subgenre to discover some postmodern archeological site that will challenge this story that we’ve left. To alter, in some critical way, the thinking about who we are and what we value. Imagine what a site like that might contain. Imagine what it might not. You can learn a lot about a species from the waste it leaves behind.

photo credits:

Mary Heather Noble

Oregonlive.com

CRAG Law Center (crag.org)

About Mary Heather

I am an East-coaster and a West-coaster. I am an academic and a creative spirit. I am an environmental scientist who always wanted to write, and a writer with a nagging nostalgia for the complexities of environmental science. Above all, I am a mother — so whether I’m writing about the natural world, family, or place, I like to consider my work as environmental advocacy in the broadest sense.

Tags

- Agent Orange

- Alkali Lake Chemical Waste Disposal Site

- Alkali Lake CWDS

- archeological site

- archeology

- barrels

- chemicals

- Dennis Jenkins

- DEQ

- dioxins

- distillation residues

- environmental archeology

- herbicides

- human coprolites

- ODA

- On What We Leave Behind

- Oregon Department of Agriculture

- Oregon Department of Environmental Quality

- Paisley Caves

- PLAYA

- PLAYA at Summer Lake

- rusting drums

- toxic herbicides

- University of Oregon

- Veterans

- Vietnam War

Recent Posts

- Five Year Mark

- On Writer’s Block: Notes from the Kitchen Island

- The Things They Carried

- Notes from a Soft Target

- On Advocacy and Love

- 2018 Moravian College Writers’ Conference

- Empathy

- The Fact of a Penis

- Labor Day

- On Hiding

- Memorial Day

- #CNF Podcast Episode 43

- Bay Path University’s 15th Writers’ Day

- On Authority and Punishment

- If There Were No Rules

- Science is a Refugee

- 2017 Moravian College Writers’ Conference

- Thanks, Food & Prayers

- Eviction

- Love Does Not Equal Silence

2014 © Mary Heather Noble. Website Design and Development by The Savy Agency.