Blog and News

The Myth of Blaming Pandora

- DateMay 13, 2015

- AuthorMary Heather

- Categories

- Discussion0 Comment

Chemicals are in the news again. Earlier this month, the New York Times reported on new concerns regarding the health effects of perfluorinated chemicals (PFCs) — a class of chemicals used to treat materials for oil, stain, grease, and water repellency, and commonly found in thousands of products such as pizza boxes, carpet treatments, footwear, sleeping bags, tents, and other everyday items (see “Commonly Used Chemicals Come Under New Scrutiny,” May 1, 2015).

PFCs have been the subject of intense debate for many years, after research confirmed the persistence of long-chain PFCs both in the environment and in people’s bodies, potentially increasing the risk of cancer and other health issues. As a result, and under pressure from regulatory agencies, DuPont removed one of these chemicals, perfluorooctanoic acid (or PFOA, also known as “C8”), from its Teflon product line, and has since replaced C8 with other chemicals.

Now the spotlight is on these replacement PFCs, known in the chemical industry as poly- or perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs). At issue is whether manufacturers should be allowed to use these second-generation PFCs in consumer products, without knowing the full-scale environmental health effects of this “new crop.” While the American Chemistry Council argues that the new generation of PFCs are safer alternatives to the chemicals they have replaced, many toxicologists anticipate negative effects from these alternative compounds, on the basis that they reside in the same family, and exhibit many of the same properties as the original toxic compounds.

The rush to replace one class of harmful substances with another “less harmful” alternative is nothing new to the American marketplace. Exhibit A: the replacement of environmentally persistent organochloride pesticides (such as DDT, aldrin, and dieldrin) with a new class of pesticides called organophosphate chemicals. Exhibit B: the replacement of tetra-ethyl lead in gasoline with methyl-tertiary-butyl-ether, or MTBE. And most recently, the phasing out of bisphenol A (BPA), in favor of bisphenol S (BPS) in common plastic goods.

But the extent to which “less harmful” is known before unleashing substitute chemicals on the American public has been, and continues to be an unfocused concept. Consider: years after their pervasive use on American food crops, organophosphate chemicals (which were derived from military nerve agents used in chemical warfare) — the supposed “safer” class of pesticides — are now being implicated in the increased incidence of neurodevelopmental conditions, as well as the increasing incidence of childhood brain cancers.

But the extent to which “less harmful” is known before unleashing substitute chemicals on the American public has been, and continues to be an unfocused concept. Consider: years after their pervasive use on American food crops, organophosphate chemicals (which were derived from military nerve agents used in chemical warfare) — the supposed “safer” class of pesticides — are now being implicated in the increased incidence of neurodevelopmental conditions, as well as the increasing incidence of childhood brain cancers.

And MTBE — once hailed as the “environmentally friendly” gasoline additive used to reduce emissions of smog-producing air pollutants — turned out to be a rogue replacement as well, a compound so soluble and mobile in the subsurface that it quietly knocked out 70% of Santa Monica, California’s drinking water wells before its toxicologic properties were really even known (see the original “60 Minutes” feature on MTBE here.) In fact, the health effects from exposure to MTBE are still being investigated, and though the EPA has identified the chemical as a possible human carcinogen, the agency has yet to establish a Maximum Contaminant Level for MTBE in drinking water.

In my own environmental remediation days, MTBE was known as a “runner” — a chemical that traveled so quickly in soil and water that its addition to gasoline pumps in the 1990s significantly lengthened the geographic footprint of gasoline plumes from leaky underground storage tanks. Perhaps the most frustrating aspect was the predictability of the scenario we saw playing out in the field. Anyone who understood the chemical properties of MTBE should have anticipated what could happen when you put a chemical like that into an underground storage tank located above a drinking water aquifer…

We have yet to understand the impacts of BPS, currently standing in for the BPA that recently leached from our baby bottles and plastic food containers, let alone the environmental health consequences of this new generation of PFCs. But we can make some educated guesses. Based upon our current modus operandi, we can be sure that we will find them in our environment, our food, and our bodies before we really know.

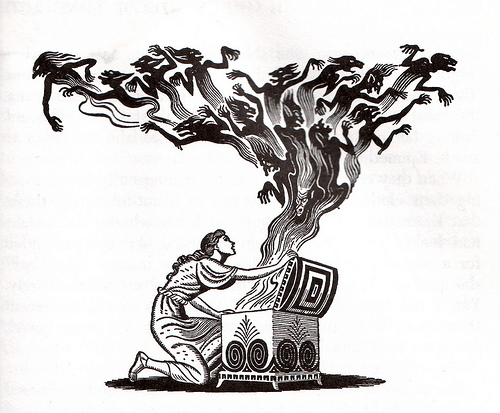

It’s all too easy to look at the presence of these chemicals in our environment, in ourselves, as some kind of cosmic event over which we had no control, like Pandora’s Box. But in so doing, we conveniently excuse ourselves from acknowledging the active role we are taking in our own self-destruction. By blaming Pandora, we abstain from the responsibility we have as intelligent human beings to anticipate these outcomes based upon 1) documented history, and 2) scientifically possible outcomes. We know damn well what can happen because we have already seen what can happen. By turning a blind eye and allowing replacement chemicals to enter the market without sufficient study, all we are doing is continuing a legacy of non-consensual experimentation. On ourselves, on future generations.

About Mary Heather

I am an East-coaster and a West-coaster. I am an academic and a creative spirit. I am an environmental scientist who always wanted to write, and a writer with a nagging nostalgia for the complexities of environmental science. Above all, I am a mother — so whether I’m writing about the natural world, family, or place, I like to consider my work as environmental advocacy in the broadest sense.

Tags

- aldrin

- bisphenol A

- bisphenol S

- BPA

- BPS

- C8

- childhood brain cancer

- Commonly Used Chemicals Come Under New Scrutiny

- DDT

- dieldrin

- DuPont

- environmental

- gasoline

- leaking underground storage tanks

- long-chain PFCs

- methyl-tertiary-butyl-ether

- MTBE

- neurodevelopmental conditions

- non-consensual experimentation

- organochloride pesticides

- organophosphate chemicals

- Pandora's Box

- perfluorinated chemicals

- perfluorooctanoic acid

- pesticides

- PFASs

- PFCs

- PFOA

- plastic

- replacement chemicals

- substitute chemicals

- Teflon

- tetra-ethyl lead

- toxicologists

Recent Posts

- Five Year Mark

- On Writer’s Block: Notes from the Kitchen Island

- The Things They Carried

- Notes from a Soft Target

- On Advocacy and Love

- 2018 Moravian College Writers’ Conference

- Empathy

- The Fact of a Penis

- Labor Day

- On Hiding

- Memorial Day

- #CNF Podcast Episode 43

- Bay Path University’s 15th Writers’ Day

- On Authority and Punishment

- If There Were No Rules

- Science is a Refugee

- 2017 Moravian College Writers’ Conference

- Thanks, Food & Prayers

- Eviction

- Love Does Not Equal Silence

2014 © Mary Heather Noble. Website Design and Development by The Savy Agency.