Blog and News

Heartache

- DateJanuary 31, 2014

- AuthorMary Heather

- Categories

- Discussion2 Comments

I never would have gotten away with writing it. Some editor would have sent it back, compelled by the story’s likeness to an awful, sentimental movie to take a few minutes of an overbooked hour to scribble in hasty annoyance: Trite use of tragedy.

And she’d be right if it wasn’t true. It was the weekend before Thanksgiving. He had just turned sixty-three the month before. Had just retired from a job he disliked a few before that. And it happened moments after he’d driven past the building where he had worked for 20 years. He was happy, finally, after many years of discontent. I think that’s what stays with me like a slow-fading bruise, like the lingering streams of vapor in the sky from an airplane long flown by. He was happy.

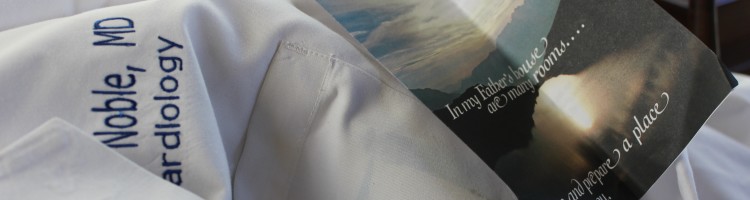

This should comfort me, but instead it slices through like tire tracks in snow —straight green lines cut into white— like the tire tracks that remained for days after it happened. Tire tracks that veered off the road, over the sidewalk, and directly into brick. Lightish brown, 1960’s municipal-variety brick — the Town’s water pump station. It had been his heart, completely unexpected. And his son, my husband, is a cardiologist.

Gavin was on-call at the hospital here in Bend, Oregon when I got the phone call from the hospital clear across the country. He’d had a horrible night, his pager repeatedly piercing the midnight air with its shrill, insistent beep. He’d gone into the hospital at 3 am. Was probably rounding on patients when his own father’s heart stopped working hundreds of miles away. Impossible. Just that morning I saw the comment that my father-in-law had written, right before he died, on the family photo I had posted online the previous night: I so love this picture. It brings tears to my eyes. A moment of weakness. Gavin’s dad rarely posted anything on Facebook. Tears were even less frequent.

My husband is just like his father. Same red hair, same temper, same posture, same fingernails bitten down to their beds. Same aura of invincibility. Same tendency, when upset, to disappear into the garage and tinker, rather than allow emotion to bubble up. He’s been spending a lot of time in the garage lately. He made an amplifier from scratch last week —circuit board and everything— and is working on another.

How does a cardiologist grieve when his father’s just died of an unexpected heart attack? When he lives hundreds of miles away and was certain he had a few more decades to diminish that space? A few more decades of talking about home-grown hops and home-brewed beer, a few more decades of sharing our girls with him, of learning about what else to expect as a dad.

The first day back to work after returning from the funeral, Gavin told me he had a patient who smoked so much that he had to wash his hands three times afterwards just to wash the smell away. I know that Gavin has many of those — people who care less about their health than he does. People unmotivated to change their habits to keep a heart attack at bay. These are the people who enrage me now, because it seems downright unfair for any of them to be living when Gavin’s healthy, 63-year-old father has just passed away. Me? I would have a hard time keeping the F— you’s from slipping out.

But my husband just goes out to the garage, clipping wires with the tools his father gave him. He doesn’t even realize what he’s doing.

It’s relatively easy for me to process my own grief: I’m a writer, so it’s okay for me to be emotional, even when I’m at work. And I can take cues from our girls, welcome the tears triggered by some harmless family tree crafting activity from an American Girl activity book. It’s okay for me to climb into their beds and hold them as we cry. It’s not as easy for Gavin. He has to stand in an Oxford shirt and a white lab coat, smile meekly while the wife of a patient expresses her condolences about his father. “Oh, Dr. Noble,” she says, “You’re so good at what you do. I hope it wasn’t his heart.”

Gavin’s been playing in a band lately, taking his home-made amplifier that he built with his father’s old tools to someone else’s garage to play. Evading his sorrow with the company of men and the sound of electric guitar. Last week they had a gig on a night before I had to leave town. —Which, I’m embarrassed to say, annoyed me. Then I found out that it was a benefit for someone from work who is facing terminal cancer.

He stayed out late, later than usual, and didn’t answer any of my calls or texts. I paced the halls at home because everyone knows that tragedies often happen in pairs. When he finally came home, I was short with him, my temper flared by our missed opportunity to debrief on the kids before I left town, by the beer I smelled on his breath. “My phone battery died,” he told me, “And I took her out for a beer.” Meaning the woman who is dying of cancer.

Maybe it was being able to do one small thing for this woman before saying goodbye. Maybe it was not being able to do either of those for his dad. In bed, finally, he whispered, “Why didn’t I catch it? This is what I do.”

I climbed under the covers and molded my body around his. Held him as he cried.

About Mary Heather

I am an East-coaster and a West-coaster. I am an academic and a creative spirit. I am an environmental scientist who always wanted to write, and a writer with a nagging nostalgia for the complexities of environmental science. Above all, I am a mother — so whether I’m writing about the natural world, family, or place, I like to consider my work as environmental advocacy in the broadest sense.

Tags

2 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Recent Posts

- Five Year Mark

- On Writer’s Block: Notes from the Kitchen Island

- The Things They Carried

- Notes from a Soft Target

- On Advocacy and Love

- 2018 Moravian College Writers’ Conference

- Empathy

- The Fact of a Penis

- Labor Day

- On Hiding

- Memorial Day

- #CNF Podcast Episode 43

- Bay Path University’s 15th Writers’ Day

- On Authority and Punishment

- If There Were No Rules

- Science is a Refugee

- 2017 Moravian College Writers’ Conference

- Thanks, Food & Prayers

- Eviction

- Love Does Not Equal Silence

2014 © Mary Heather Noble. Website Design and Development by The Savy Agency.

So sad but so well written.

It’s crafted beautifully and honestly Mary Heather. Moved in my mind like a narrated film and makes me miss you all the more. I am proud of you and remember the day you quit your job to pursue your dream. Here you are! You write like you live – passionately. Wishing you all the best!