I know that’s what you’re thinking. It would make sense, wouldn’t it? I am, after all, a somewhat anxious person. I worry more than I probably should about my kids’ health and safety. I worry about their future. I am consumed with the cancer struggles of a few of my friends. And I suppose my predisposed concern about the effects of climate change, or my family’s exposure to the chemicals in our water, food, and household products has been reinforced, to some degree, by my time spent as an environmental regulator.

It’s like what they say about going out to eat with a former restaurant worker: sometimes a behind-the-scenes view will compel you to eat in. I can predict with some measure of certainty, the places around town that are most likely to be contaminated. I have worked in the slow grind of bureaucratic oversight —where the caseloads are often so vast and complex that the first order of triage is literally whether someone is eating or drinking pollution— and I have tasted the sometimes contemptuous nature of corporate citizenship. In other words, I know the science behind how real environmental messes happen, and the long, uphill battle of righting those past mistakes. I know how much can get missed.

I guess that’s why, when I hear headlines and statements attempting to diminish what I consider to be legitimate issues of public concern, I get a little defensive. You know what I’ve talking about. Headlines like this: Will 2016 Be a Climate Hysteria Election? Or this: Fracking Opponents Ditch Science, Embrace Hysteria. A condescending tone is the common thread, as if the environmental and public health hazards of climate change, or fracking, or exposure to toxins is something unfounded, imaginary. As if no peer-reviewed data substantiating these threats exist at all. As if there weren’t already well-documented stories of significant environmental harm.

Let’s deconstruct this concept: hypochondria is an ancient Greek term, referring to the soft, vulnerable area below the rib cage, which, until the early 18th century, was believed to be the source of malaise, the place in the body where illness is borne. And though the term has since evolved to represent a more psychological phenomenon — that is, a person’s unfounded fear that he or she has a disease, or is about to develop one — I think it’s worth noting that the original term refers to the place where you might feel your broken heart.

But like many things involving emotion in Western culture, hypochondria has assumed a pejorative meaning, an insult to the person claiming to be sick, an accusation of mental illness. Like hysteria, an equally loaded social label, but perhaps even more so because of its gendered root: “hustéra,” the ancient Greek term for womb. Hysteria, as in the female version of hypochondria, a nervous condition caused by “suffering in the uterus” — indeed, the source of the crazy being femininity itself.

Rachel Carson was called a hysterical woman. Carson, a scientist who concealed her own breast cancer for fear that the chemical industry would not allow her scientific findings to transcend her personal plight. Turns out, the science would prevail. And the interesting irony is that it was her gift of harnessing our collective emotion that made us look at the science in the first place.

Many feminist scholars have argued that the label of hysteria was a social device aimed at restricting the full participation and expression of women in a male-dominated society — and I’m not sure that the big-industry response to our most pressing environmental issues is all that different. There is money and power to be lost, after all, by granting attention and care to legitimate scientific concern. Much easier to classify the concerned as “crazy” or “emotional,” carve them out as something different than normal sentient beings.

Like, for instance, the comments uttered last week by Averil Macdonald, the newly-appointed chair of the fossil fuel industry’s lobby group, UK Onshore Oil and Gas. “Women, for whatever reason, have not been persuaded by the facts,” she said, “More facts are not going to make any difference.” The implication, of course, is that most women don’t understand the science behind fracking, and instead base their concerns purely on their emotions. Read: concerns = emotional = crazy = unfounded.

But there’s a problem with this equation and it’s the science itself. Macdonald’s comments have unleashed a fury of social media responses from women scientists under hashtag #FrackingGirlFacts, created by anti-fracking activist Sandra Steingraber, a scientific expert and author of many books on the links between human health and the environment. Notwithstanding the emotional hardships of a family’s loss of property value from fracking activities in their neighborhood, or a community’s loss of potable water from fracking-related ground water contamination, there are many un-emotional, scientific studies that have identified real risks associated with fracking. Ground water contamination. Air pollution. Toxic exposure. Fracking-induced earthquakes and degradation of infrastructure. The list goes on.

—Which is my point. I do not regard concerns about climate change, or fracking, or exposure to environmental toxins as hysteria or hypochondria because the concerns are not unfounded. Legitimate data do exist. And perhaps the thing that we’re getting so emotional about is the manipulation of those facts in the first place.

Or maybe we’re just emotional because we truly understand what is at stake. Carson was one of the first to successfully convey that message, the first to shine a light on the intersection of environment and health, the first to employ science and emotion to motivate a change. Maybe she looked at what was happening and felt her heart breaking in that soft, vulnerable area below her rib cage. I feel that sometimes, too, because I also understand the science.

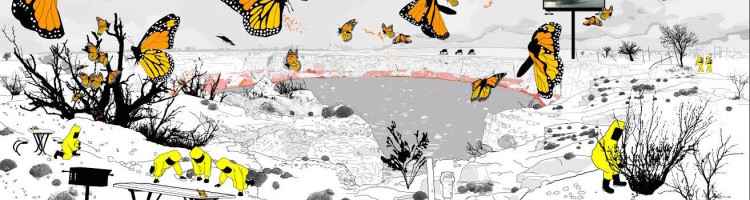

Image credit: “Mesocosm (Wink, Texas)” by Marina Zurkow, www.marblehouseproject.org