Blog and News

Making Science Read Like a Thriller: Use of Fictional Plot Structure

- DateSeptember 28, 2013

- AuthorMary Heather

- Categories

- Discussion0 Comment

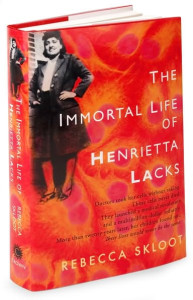

in Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks is an immersive journalism work that reveals the history of the first laboratory-grown human cells, the birth of a multi-billion dollar medical research industry, and the life and death of the African American woman from whom the first cells were taken. The Immortal Life is richly informative, educating its readers about the science behind cell culturing for medical research, and discussing an array of controversial subjects that emerge from the story, including institutional racism, socioeconomic discrimination, inequities in the American health care system, bioethics, and ownership of human tissue and intellectual property. But what has made The Immortal Life such a resounding success is not just its capacity to enlighten; rather, it is the fact that the book does so in a form traditionally reserved for fictional novels. This literary craft blog post explores how Skloot uses elements of fiction to turn a scientific journalism piece into a provocative best seller.

Though the initial vision of The Immortal Life was to tell the story of Henrietta Lacks’s life — to put a name and a face on the cells that revolutionized modern medicine — the real plot becomes Skloot’s very pursuit of the story, and the Lacks family’s struggle to accept what happened to their mother, sister, cousin and friend. Henrietta Lacks was a poor black woman raised on a tobacco farm in Clover, Virginia. She was a wife and mother to five children, and at age 29, developed an aggressive form of cervical cancer. In 1951, during the brief and ultimately unsuccessful course of her treatment, doctors harvested Henrietta’s cancerous cells without her knowledge or consent — cells that would become the foundation for vaccine development, cloning, gene mapping, and other medical breakthroughs. Her family was unaware, until 20 years later when Henrietta’s identify and connection to the HeLa cell culture was leaked.

Skloot structures her narrative into three distinct sections correlating with the life, death, and immortality of Henrietta’s cells, but develops her storyline mirroring the “Freytag’s pyramid” structure often seen in novels and film. She begins with an introduction to Henrietta Lacks and her desire to tell Henrietta’s story. Skloot’s initial attempts to contact and research the family are wrought with obstacles (anger, distrust, and ignorance about the magnitude of Henrietta’s sacrifice); we are immediately hooked into the narrator’s long and dramatic journey to uncover the truth behind the HeLa cells. Intertwined in Skloot’s detective journey, and equally if not more compelling, is the Lacks family’s story, particularly that of Henrietta’s only living daughter, Deborah. It is a story of abandonment and longing, enlightenment of the past, and understanding and acceptance of what happened to the mother she never knew. Interestingly, Skloot and Deborah become antagonists and heroines in each other’s plots: Deborah is both the obstacle and the key to Skloot’s successful pursuit of the HeLa story, her suspicious gatekeeping to valuable family information fueling the dramatic tension throughout the piece, until Skloot finally reaches her breaking point in the climax of her story:

Then, for the first time since we met, I lost my patience with Deborah. I jerked free of her grip and told her to get the fuck off of me and chill the fuck out. She stood inches from me, staring wild-eyed again for what felt like minutes. Then, suddenly, she grinned and reached up to smooth my hair, saying, “I never seen you mad before. I was starting to wonder if you was even human cause you never cuss in front of me.” (p. 284)

Shortly after the confrontation, Deborah gives Skloot access to her mother’s medical file, unlocking secrets vital to Henrietta’s story.

In Deborah’s story, Skloot directly opposes Deborah’s self-protective desire to suppress the details about Henrietta’s life. Skloot’s investigative persistence forces Deborah to confront painful details about her mother’s illness and death, the institutionalization and death of her mentally disabled sister, and the abuse and neglect Deborah and her siblings experienced in the wake of Henrietta’s death. At the same time, Skloot serves as Deborah’s hero, teaching her the science and history behind Henrietta’s contribution to medicine, ultimately empowering her to retain ownership of the Lacks family heritage and protect their story from future exploitation.

The climax to Deborah’s story occurs at toward the end of the book, shortly after she has given Skloot her mother’s medical file. Deborah has broken out into hives from the stress of the entire experience, and they return to Clover, Henrietta’s hometown, and the home of Deborah’s preacher uncle, Gary. At Gary’s home, as Deborah careens toward an emotional breakdown, Gary intercepts with a religious healing ritual to relieve her of the emotional burden the HeLa cells carry. With an exorcism-like passion, Deborah pleads:

“Thank you Lord for giving me this information about my mother and my sister, but please HELP ME, cause I know I can’t handle this burden myself. Take them CELLS from me, Lord, take that BURDEN. Get it off and LEAVE it there! I can’t carry it no more, Lord. You wanted me to give it to you and I just didn’t want to, but you can have it now, Lord. You can HAVE IT! Hallelujah, amen.” (p. 292)

The scene ends with Gary’s symbolic transfer of the burden of the HeLa cells from Deborah to Skloot, marking the resolution of both of their plots. The reader is left breathless — not only from a behind-the-scenes tour through the murky bioethics in the history of medical research, but from the emotional punch packed into the two women’s personal stories. Had Skloot not elected to make herself a character in The Immortal Life, and employ the elements of fiction to transport the science and social history, the book might not have ever taken flight.

About Mary Heather

I am an East-coaster and a West-coaster. I am an academic and a creative spirit. I am an environmental scientist who always wanted to write, and a writer with a nagging nostalgia for the complexities of environmental science. Above all, I am a mother — so whether I’m writing about the natural world, family, or place, I like to consider my work as environmental advocacy in the broadest sense.

Tags

Recent Posts

- Five Year Mark

- On Writer’s Block: Notes from the Kitchen Island

- The Things They Carried

- Notes from a Soft Target

- On Advocacy and Love

- 2018 Moravian College Writers’ Conference

- Empathy

- The Fact of a Penis

- Labor Day

- On Hiding

- Memorial Day

- #CNF Podcast Episode 43

- Bay Path University’s 15th Writers’ Day

- On Authority and Punishment

- If There Were No Rules

- Science is a Refugee

- 2017 Moravian College Writers’ Conference

- Thanks, Food & Prayers

- Eviction

- Love Does Not Equal Silence

2014 © Mary Heather Noble. Website Design and Development by The Savy Agency.